If you study history it is almost impossible to tell when a civilisation or a city began to die. If you quiz 5 historians you will get 5 different answers.

When did the British Empire end in India?

India gained independence from the British on the 15th August 1947. But…

Truth be told, that was the day the actual handover took place. The discussions on the same had started way back in 1945. The reason those discussions even got tabled was because England had won a pyrrhic victory against the Germans in the Second World War. They were neck-deep in debt to the Americans and had to concede to all American demands after the war. Many American thinkers thought Britain should free India. But…

Some historians say that the First World War had already hollowed out British wealth. Woodrow Wilson already had his hands on the British jugular because of the loans the American public had extended to the British. The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre in 1919 cemented the demise of the Empire in India. The only reason Gandhi was able to pursue non-violence as a path to independence was because the British had already given up.

I am sorry for that heavy digression. The point is… I am going to make a point.

When the Pandemic started, every white-collar worker continued to work like nothing was even going on. They went about life as usual. Products were launched, sales targets were met, growth was registered, and it was as if the office was totally unnecessary.

The death knell for commercial real estate was sounded.

Now, in New York, for instance, 24% of the real estate is commercial. Mostly offices, these spur other commercial real estate like retail, restaurants, etc. In fact, it is this clustering that gives us the Commercial Business District (CBD) or the beating heart of most modern cities.

If people do not work in these offices, the retail space loses value. If there is no retail or office functioning, who would even go to the CBD?

The pandemic ended, insofar as all of us were not masked up all the time. Most of those workers never returned to the office. Businesses continued to pay the lease, hoping to go back to normal. At some point between 2021 and 2022, offices started shutting down. Leases that came up for renewal were not renewed.

At this point in 2023, it would be safe to say that almost ALL white-collar workers are in some kind of hybrid work mode. Many are still in FULL work-from-home mode and even the slightest suggestion of using the office again results in revolt.

Amazon employees staged a protest this week over the company’s return-to-office mandate. The tech giant doesn’t seem too bothered by it.

“We’re always listening and will continue to do so, but we’re happy with how the first month of having more people back in the office has been,” Amazon spokesperson Brad Glasser told Fortune.

In February, CEO Andy Jassy sent a memo saying remote workers should return to the office on May 1. “We should go back to being in the office together the majority of the time (at least three days per week),” he wrote.

Source: Yahoo!

Google recently implemented changes to its hybrid office policy, introducing badge tracking and emphasising the inclusion of attendance in performance reviews. Furthermore, employees who were previously granted approval for remote work may now face a re-evaluation of their remote status.

According to discussions with employees and internal posts on a site called Memegen, Google is experiencing a rising level of apprehension among its staff regarding the extent of management’s control over physical attendance, reported CNBC.

Employees express feeling like they are being treated akin to schoolchildren. Additionally, there is mounting uncertainty among those who relocated to different cities and states after receiving permission to work remotely, as they ponder what the future holds for them.

Source: People Matters

In almost all of the cases, the companies are demanding a partial return to office ranging from 2 to 4 days a week depending on the organisation.

Safe to say 5 days a week at the office has been bid farewell.

Hybrid work is here to stay

The Work from Home to Work from Office spectrum is born. Everyone seems to only be debating how much time at the office is fair.

Some of this conversation is coming back to how strong the home roots are for many people. A person, originally from Philadelphia may have been working in New York but if their roots back home were strong, the Pandemic would have caused them to return back. This is true for many tech workers. If for 3 years it did not matter that he/she was not in New York, why return?

The cities with the most number of non-natives are beginning to take a hit. None more so than New York.

Today, three years after the pandemic emptied office buildings nationwide, Rechler has been forced to reckon with the possibility that the buildings that were worth so much not so long ago may now not even be worth keeping. Corporate tenants are typically locked into multiyear leases, which guarantee stability in the commercial real-estate market for a time. But every month, more leases expire, giving tenants an opportunity to rethink their space, and every day, employers are staring at empty desks. Many companies, which had been trying to squeeze more workers into less space for years, are not renewing. That leaves an office landlord facing hard choices. What should Rechler do, for instance, with 5 Times Square, a million-square-foot building that 20 years ago was a gleaming centerpiece of 42nd Street’s revival? After the departure of its longtime anchor tenant and major renovations, it’s currently close to empty.

Not long ago, real-estate industry leaders were urging the city’s workers to return to their office buildings. Rechler told me in 2020 that it was a “civic responsibility.” They’ve since surrendered to the changed reality. Sometimes tenants are downsizing and upgrading to more expensive spaces; sometimes they are economizing under the guise of offering flexibility. From the landlord’s perspective, motive hardly matters — space is space, and it’s got to be rented. Add in sharp hikes in interest rates, which make refinancing a huge commercial mortgage a potentially ruinous proposition, and you have a crisis that threatens not just the solvency of office buildings but the loans that are attached to them and the banks that hold them and, by extension, the whole economy.

[…]

According to Cushman & Wakefield, Manhattan’s office-vacancy rate is around 22 percent, the highest recorded since market tracking began in 1984. When you include sublet space, more than 128 buildings in Manhattan currently list more than 200,000 square feet of space as available for lease, according to data from the firm CoStar. The available space in these buildings alone amounts to more than 52 million square feet: the equivalent of more than 40 skyscrapers the size of the Chrysler Building. Certain areas and building types are particularly endangered — the Garment District lofts once favored by tech start-ups, the generic glass gulch of Third Avenue in the 40s and 50s — but the pain is widely distributed. Many large property owners are now performing triage, trying to determine which buildings are still worth anything like what they paid for them. In Rechler’s case, this reassessment has taken the form of a process he calls “Project Kodak,” after the once mighty film-and-camera company. He classifies buildings that are worth saving as “digital.” The duds he deems “film.”

Source: Curbed

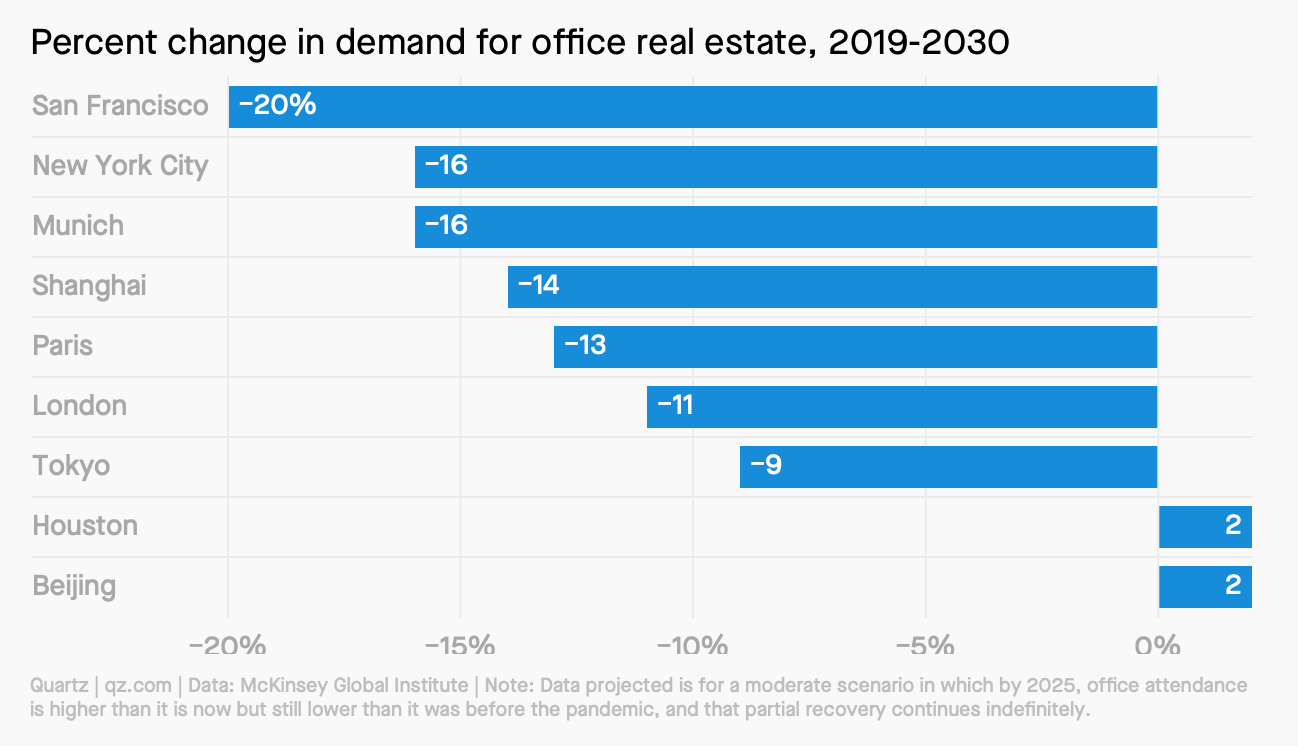

And it is not just New York which is in trouble there are also other cities that are in trouble in terms of commercial real estate.

Now the report puts a number to residential losses overall: From mid-2020 to mid-2022, New York City lost 5% of its urban core population, and San Francisco lost 6%.

Although employers are attempting to call remaining workers back into the office, remote and hybrid work has staying power. Today, urban office attendance is still down by 30% from pre-pandemic levels, although numbers vary by city, industry, and neighborhood. For example, workers come into the office about 3.1 days in London per week, while it’s about 3.9 days in Beijing.

Source: Quartz

But you see it does not end with this. There are restaurants, pubs, and all kinds of retail businesses that depend on the number of people working in a region. If 20% of the people who used to frequent an area disappear consequently a lot of these businesses are forced to shut down. Then people who supply these businesses start to go. So there are several second-order, third-order and even fourth-order effects. Think about the number of cabs that were required in the region earlier and now.

The above graphic also makes me think, the more expats in a city, the harder it has been hit.

So what can they do?

McKinsey predicts a 26% drop in office property values from 2019 to 2030, which is in the ballpark of $800 billion when adjusted for inflation. Again, that’s just a moderate read: In a severe scenario, the consulting company says the plunge could actually be as steep as 42%.

Source: Quartz

The financial value is one facet of the issue. To be honest, most of the people who will take this hit will be capable of absorbing it. In most cases, it seems like Banks will be left with lots of these properties that have been collateralised. Many of the owners would rather let the banks repossess the property than pay off the loans. So after the sub-prime lending crisis, we might be introduced to the super-prime lending crisis. These would have been considered extremely secure loans!

Cities are trying to redo their buildings to put them to other types of use.

New York City officials announced plans on Thursday to ease the conversion of office buildings to housing and to open manufacturing areas south of Times Square to new residential development, as part of a broader push to reinvent the struggling business district in Midtown Manhattan and address the city’s housing crisis.

The plans, outlined by Mayor Eric Adams at a news conference in a vacant office building, would allow for more housing to be built by rezoning manufacturing areas between 23rd Street and 40th Street from Fifth Avenue to Eighth Avenue. A separate plan focusing on conversions of office buildings into residential could allow for 20,000 new homes, the city estimates.

Source: NYT

The problem is architectural. Office buildings are developed with large floor plates spanning thousands of square feet. Turning them into homes means giving each room ventilation, light, water supply, etc Office buildings are essentially floors sheathed in glass on all sides. The only openings are meant for elevators. This is going to be difficult to pull off.

The Death of a City

I am not saying New York is dead. But maybe it is beginning to die. Also, this piece has focused a lot on New York because there is a lot of focus and data about the city. This may be the case for some of the largest cities in the world.

- The nature of work is changing and many of the knowledge workers will never ever return to working in the office 5 days a week.

- This has caused a significant shift in the demand for office spaces

- For many, just being able to avoid the traffic of large cities is reason enough to choose to work from home.

- People are also beginning to shift away from large cities.

The ONE thing that the pandemic showed us was that cities are excellent vectors for the transmission of diseases. Cramming 10 million people into 300 square kilometres, like New York does, is how you ensure that diseases spread as fast as possible.

Large cities are falling out of vogue.

What might be the fate of such cities?

Going back to where I started this piece, in hindsight you might find different points or events that served as the beginning of the end. Maybe 2020 is the beginning of the end, maybe it is not. Maybe after all this, it may still bounce back! Perhaps another black swan event might push these cities over the edge.

It is hard to be certain, but it would take a die-hard optimist to imagine a future where these cities grow even larger than the high water mark set in 2020.

Leave a Reply